At the beginning of April, 2014, I went on a three-week research trip to India. On the first part of the journey, I travelled with Jelle Bouwhuis to New Delhi, Baroda and Bombay. On the second part, I went to Bengaluru, Kolkata and again to Delhi.

The aim of this trip was to get in touch with and learn more about the contemporary art scene in India. My three-week trip coincided with the start of the country’s month-long national elections, and many of my conversations with local art professionals eventually touched on the possibility of historical change. That change loomed on the roadsides, literally, by way of countless billboards depicting Narendra Modi, the popular presidential candidate of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), India’s right-wing, Hindu nationalist party.

New Delhi

When we arrived in Delhi, a city of 22 million inhabitants, summer had just begun. The incessant traffic immediately closed in on our ambitious schedule of studio visits and meetings. A highlight of the first day in Delhi was our visit to the National Gallery of Modern Art, an extensive museum complex with several exhibition galleries showing the development of modern Indian art and its relation to traditional culture. To this end, a selection of 10th-century miniatures was displayed in the first gallery, alongside paintings by modern masters, so that formal references become traceable. The wall texts underscored the relation of Modern Art in India to local traditions of imagery and/or literature. In some paintings, I recognized familiar buildings, such as the Red Fort, which I had seen during an early morning bike ride through Old Delhi and towards the Yamuna River.

A day later, the Yamuna again drew my attention, when we visited the studio of Ravi Argawal, an artist, environmental activist, writer and curator. Argawal is deeply concerned with the pollution of the Yamuna River, and the resulting decline of life in and around it. He has devoted years of his life to observations of the river and its surroundings. In 2011, Argawal’s engagement with the Yamuna led to The Yamuna-Elbe Project, a festival to which he invited others – including many artists – to participate in a celebration of the river.

On our third day in Delhi, the Khoj International Artists Association appeared to me as an oasis of a venue in the midst of a run-down part of the city, bustling with people and livestock, yet located not far from a popular, high-security, luxury shopping complex. Khoj is a contemporary art centre with an international residency programme. We were warmly welcomed by director Pooja Sood and her assistant, with a cup of chai, over which Sood told us about the history of Khoj, constantly referring to a massive (!) book with information about Khoj’s activities since its establishment in 1997. Khoj is located in a dusty street, but its clean, gleamingly white building functions as a small-scale research centre with a library, computers and a café. Only on the rooftop terrace, looking out onto the neighbouring decay, were we reminded of the conditions that people deal with in this part of town, where disintegrating houses are not just an inspiration for artists, but a threat to people’s lives.

Later on in Delhi, we came across an example of a work inspired by Khoj’s location, by Pavalli Paul. The Posthumans Were Here is a video work made during her residency at Khoj, in November, 2013. The Posthumans Were Here was part of her studio installation of the same title, which also included sculptural objects in showcases. Paul explained the objects – I remember a picture of a mud-encrusted rubber glove – as being archaeological specimens discovered by people in the future, whom she called ‘posthumans’. The video was made of found and self-shot film and video footage, all edited together, sometimes in overlapping layers. The recordings were all made on the Khoj rooftop terrace.

Displays at Sanskrit Foundation in Delhi, 2014.

There were many highlights during our four days in Delhi, including the visit to the Sanskriti Foundation and the Crafts Museum, meetings with T&T (Thukral & Tagra), the Raqs Media Collective, and Ghulam Mohammed and Nilima Sheik.

Ghulam Mohammed and Nilima Sheik in Delhi, 2014.

Our schedule also included a one-day-trip to Baroda (also known as Vadodara), a city of about 1.5 million inhabitants in the state of Gujarat, whose Chief Minister, until he recently became Prime Minister of India, had been Narendra Modi.

Baroda (Vadodara)

In Baroda, Karishma D’souza welcomed us and accompanied us on a full day of visits to artist’s studios, the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery and the Faculty of Art of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. While driving from one location to the next, our conversation repeatedly returned to Narendra Modi. His ubiquitous representations on billboards and TV screens made it impossible to avoid him as a topic. In his election campaign, Modi had won the sympathies of many Indians who believe that he is the driving force behind Gujarat’s flourishing economy. Discontent with the country’s national economic development and frustrations over the politics of the Congress Party have shaped Modi’s image and success. His record, however, is not as clean as his images suggest; the Gujarat Riots took place in 2002, when he was Chief Minister of the state.

The Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery shows Indian and international crafts and art in dusty Victorian glass cases, as well as a section called European Civilization.

Entering this section felt like being transported back in time, into a late 19th-century salon. Dozens of paintings are distributed all over the red, fabric-covered walls, with classical marble statues on the wooden floor. Despite the valuable collection of paintings on display, the exhibition spaces are in a critical state, with plaster falling from the walls and no climate control.

Later on, strolling over the campus of Maharaja Sayajirao University’s Faculty of Art reminded me of my art school days in the Netherlands: groups of young students sitting around, engaged in conversation while sketching out some ideas. Around the sculpture department, a kind of graveyard of less-successful sculptures had accumulated, and in the group studios, students were immersed in drawing models. Everywhere, there were casts of Western and Eastern classical figures.

Most of the artists we met that day are former students of the university’s Faculty of Arts. One was Roshan Chhabria, whose drawings depict figures involved in different activities, sometimes in combination with drawn letters that form words, put in homely spatial environments that accommodate them. Some of the figures have pentimenti that tell about the artist’s earlier attempts to draw them differently. These lines somehow suggest movement, making the drawings appear like snapshots, as if the figures would move on again as soon as they were drawn. Rohan’s drawings are built up of layers. They tell about how the artist perceives and makes sense of the world.

Drawing by Roshan Chhabria.

Mumbai (Bombay)

During our three-day stay in Bombay, we met with Atul Dodiya, Sahej Rahal, Reena Kallat, Shilpa Gupta and Ranjit Hoskote. Our agenda also included visits to Catterjee & Lal, Gallery Chemould, Clark House Initiative, the National Gallery of Modern Art and the Prince of Wales Museum. On our way from the airport to our hotel, we passed the Antilla building, reputedly the world’s most expensive residential property and a world-famous icon of contemporary architecture. Most of the museums and contemporary art galleries we visited are in the Colaba district. We also visited Bandra, where, amongst many other artists, Jitish and Reena Kallat and Shilpa Gupta have their studios, and Ghatkopar, where Atul Dodiya’s studio is based.

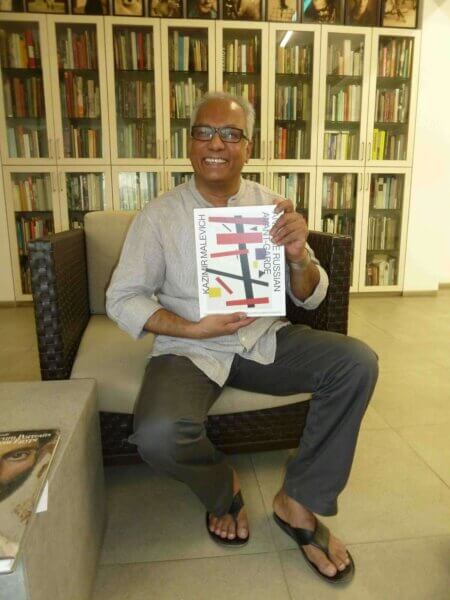

Atul Dodiya’s studiois in a much more modest skyscraper than Antilla, but it offers views of a huge area of the city, including the slums that inspired Slumdog Millionaire and buildings that symbolize the importance of the financially powerful parts of the city. Atul Dodiya’s success in the international art world is mirrored in his tidy studio, with its air of entrepreneurship and all the equipment needed for the production of works of art. Dodiya is inspired by Kasimir Malevich, a fact reflected in many of his works and solo exhibitions, including Malevich Matters and Other Shutters.

Atul Dodiya in his studio, 2014.

Dodiya’s work is represented by Gallery Chemould, one of Bombay’s oldest contemporary art galleries, founded in 1963 by Kekoo and Khorshed Gandhy, and now successfully directed by their daughter Shireen Gandhy. When we visited, the group exhibition Aesthetic Bind | Floating World,curated by Geeta Kapur, was on view.[4] Shireen Gandhy walked us through it while recounting the stories that inspired each work on display.

Not far from Chemould, theClark House Initiativeis located in a former pharmaceutical research facility, which also once served as storage for antiques and as the offices of the Thakur Shipping Company. Sumesh Sharma and Zasha Colah set up the Clark House Initiative in 2010, as a union of artists and curators, and as an alternative to the commercial galleries and museums. Clark House is now an exhibition space and a kind of headquarters for Sharma and Colah and the artists with whom they collaborate on local, national and international levels. Broadly speaking, Sharma and Colah’s curatorial practice is marked by an interest in the relation between art and politics from contemporary and historical perspectives. They are particularly engaged in the disclosure of otherwise under-represented art historical narratives. The connection between the Clark House Initiative and the Stedelijk Museum will be further developed in the course of this year, with the aim of setting up an exhibition project in Bombay and Amsterdam.

This blog post was first published on the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam Global Collaboration online platform in June 2014.