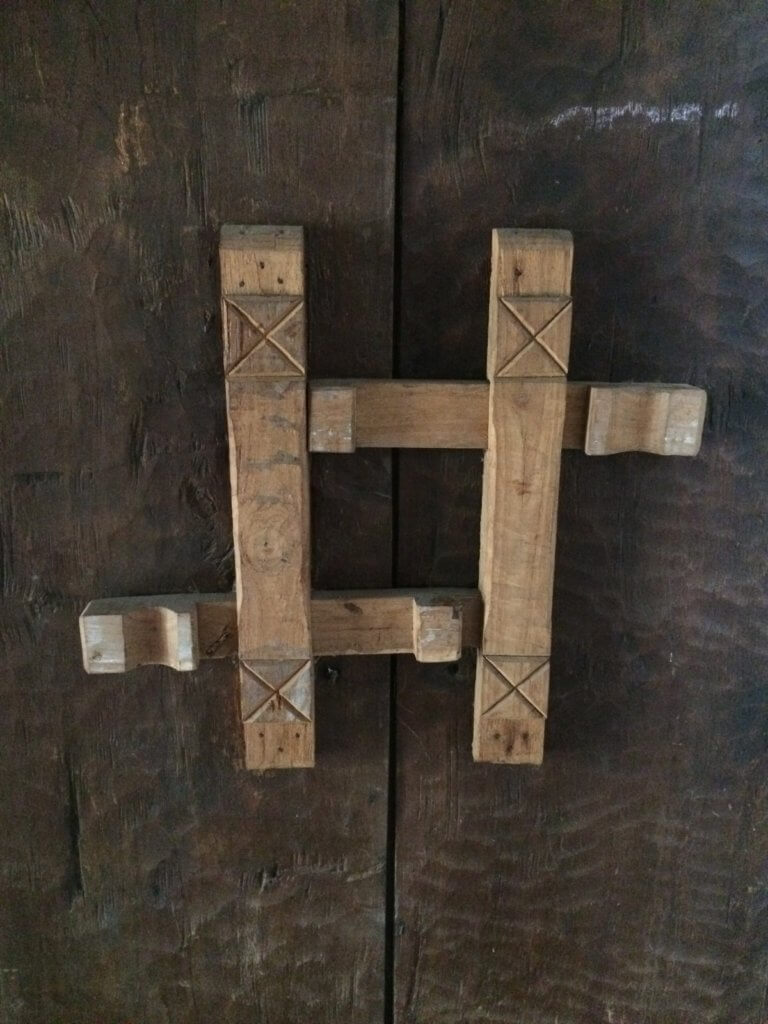

Entering the Haji Widayat Museum in Mungkid felt like kissing a princess awake from a deep slumber. When we arrived, the heavy wooden doors were open, but elegant wrought-iron gates prevented us from entering. My friend and I almost went away, but then our “hellos” must have stirred the guard from his siesta, and he let us in. The next moment, my friend rushed to the restrooms and I stood in the entrance hall, looking around curiously to take it all in, when I heard sluggish footfalls coming closer. When I turned around, a guy sat down behind the gigantic, dark wooden desk and sold me an entrance ticket.

The museum was built in the 1990s at Widayat’s own initiative, with the support of family and friends. Before his death in 2002, Haji Widayat tried to ensure the maintenance of the museum for the future and yet, the hot and humid atmosphere of the tropical environment makes the preservation of the museum and its art challenging.

The Dutch art historian Helena Spanjaard and the Indonesian collector Oei Hong Djien, who owns many paintings by Widayat, have both published extensively about their friendship with the artist, his work and their perception of it.

Spanjaard explains that “the basis of Widayat’s art came from his inner world” and that “his oeuvre [..] fits perfectly in the many traditions of the east in which the inner experience is considered as important as the material world” (Spanjaard, H. & Oei Hong Djien, Pioneer Number Four: H. Widayat, exhibition catalogue, 2014, p. 59). This focus on the inner experience is perhaps what lends originality to Widayat’s work, which stands out formally and thematically when compared to the work of his contemporaries. Unlike many other successful artists from Indonesia, Widayat never went to study in the West. Between 1960-62, he studied ceramics, graphics, landscape gardening, and ikebana in Nogoya, Japan. Other important experiences that marked his artistic production include being brought up by a mother who was a specialist in the Javanese batik technique as well as the time he spent as an administrator on plantations in Sumatra (1939-42).

In the museum, the diversity of artistic materials used by Widayat becomes apparent. A range of ceramic and wood sculptures are combined with paintings and displayed in the architecture that was designed to house Widayat’s own artwork and his collections of paintings by his artist friends. The museum furniture has been chosen with great care to optimize the visitors’ experience of the displays. Outside the main building, the artist has laid out a garden landscape that integrates ponds, two joglos, many sculptures, and some royal cages with roosters.

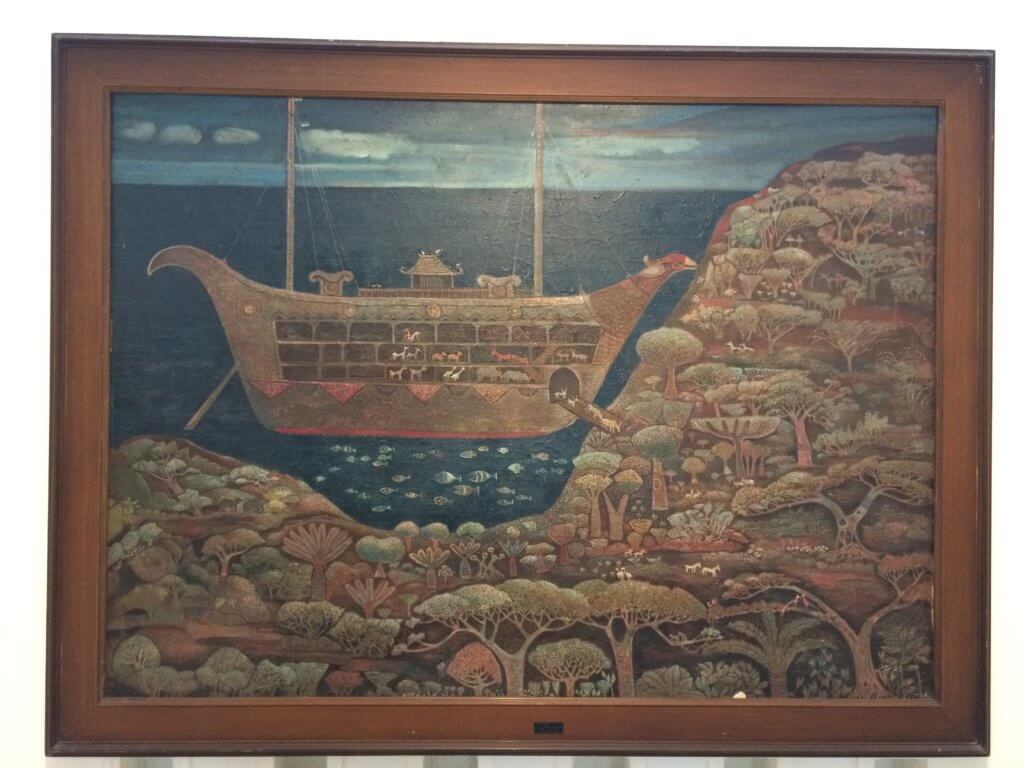

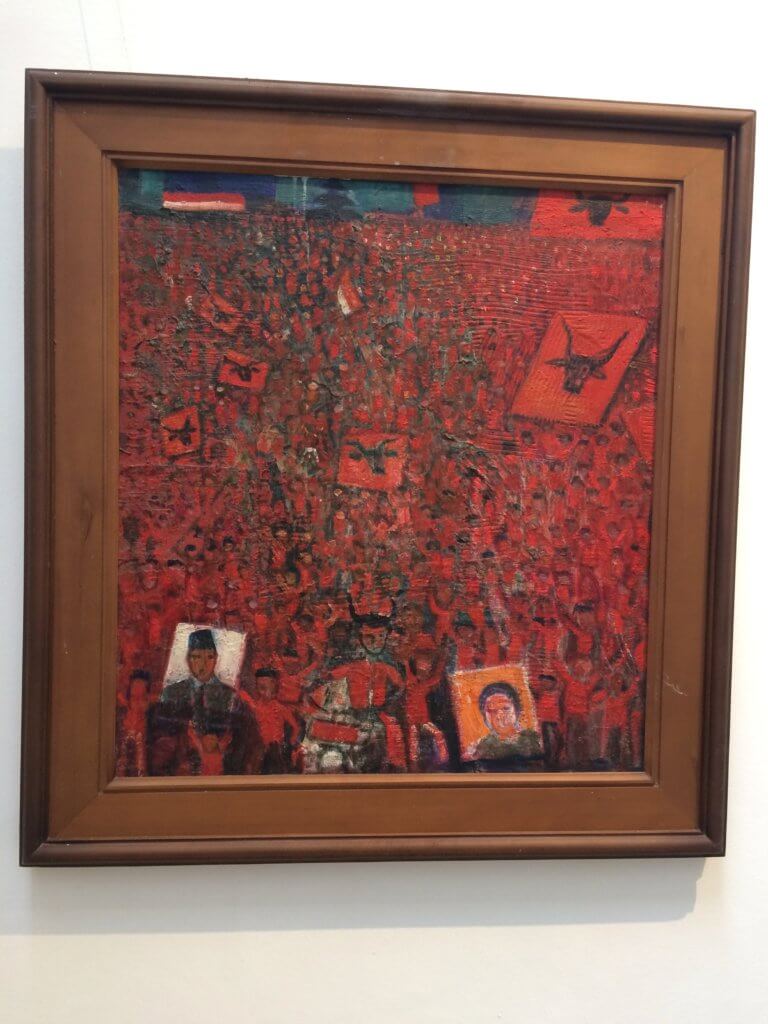

Widayat’s best paintings have decorative elements executed with patience and precision, integrated in carefully arranged compositions that occupy the entire canvas, collapsing the difference between foreground and background. Every depicted thing or organism appears equally important. Spanjaard accurately identifies several recurrent themes in his paintings: “tropical flora and fauna, primitive life, mythology, daily life, family life, and the peaceful coexistence of human beings with flora and fauna.” Looking at the paintings, I can notice that many of the compositions are still quite recognizable, even though the climate conditions in the museum have accelerated their decay. One need not be an educated restorer of paintings to see that the beauty of paintings like Kapal Nabi Nuh (1979) lies somewhere behind layers of dust and insect feces that have accumulated over the scenery Widayat imagined.

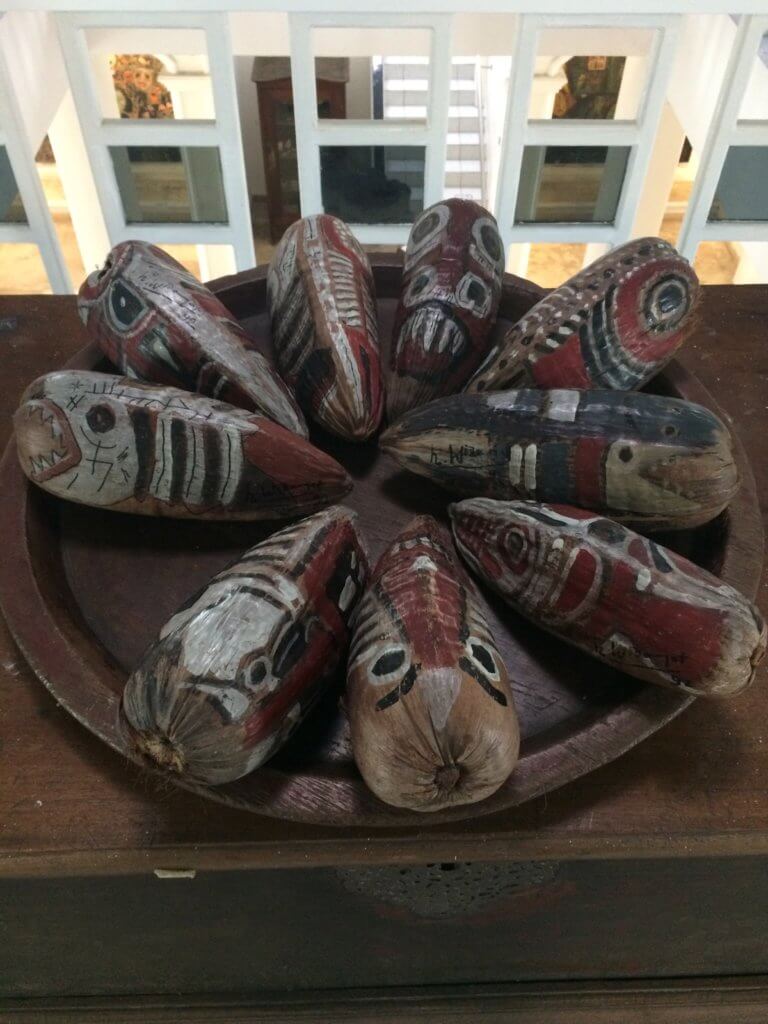

To my surprise, the Widayat Museum features several of the artist’s ceramic works. I had not known that he worked with this medium at all. Widayat’s paintings can be found in collections all over Indonesia, but I haven’t seen his ceramics anywhere else. In the museum, however, I get the impression that this was one of Widayat’s favorite media. The ceramic sculptures are executed with great attention to detail and skill and characterized by wonderful and often baffling formal language. Could it be, I wonder, that when working with ceramics, the artist felt free to indulge in liberation from the rectangular constraints of the canvas?

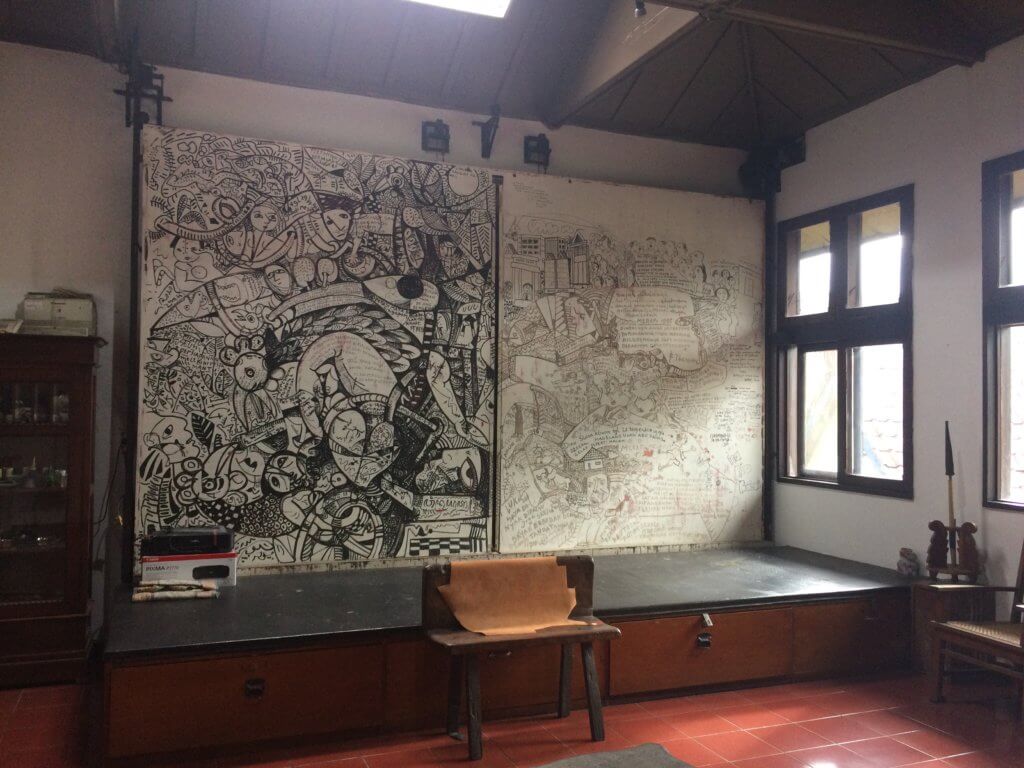

The Widayat Museum gives visitors a good impression of the artist’s oeuvre and the broad range of his artistic skills. A few years after the artist’s death, one of his sons removed almost all paintings from the museum in a stealthy mission by night, in order to sell them. His activities were stopped by the police and the case went to court. Most of the paintings were returned, but the museum has been in financial difficulties ever since. The family is still quarrelling about how to deal with their father’s legacy. Despite the current state of affairs, the gardens and the collection of ceramics are astonishing and well worth a visit. By opening up Widayat’s studio to the public, the museum offers rare and valuable insight into how the artist worked and the fruits of his labor. Widayat could only hope that his family and friends would be powerful enough to ensure the endurance of his creations and creative spirit against the power of the tropical climate and the indifference of some family members to his wishes.

My field trip to Indonesia was supported by the AFK (Amsterdam Fund for the Arts) and the Mondriaan Fund.