In October 2017, my research about the role of artists during the Indonesian independence movement brought me to Magelang, a town in Central Java of about 120,000 people. One of these people is Dr. Oei Hong Djien, an art collector and energetic supporter of the Indonesian art scene. Oei Hong Djien is a trained medical doctor, but he gave up his practice after his wife passed away in 1992. He completed his postgraduate degree in Holland in 1968, before returning to Indonesia to take over his father’s tobacco company in Magelang.

Magelang is located in Central Java province, not far from the 9th-century Buddhist temple Borobudur, the world’s largest. Even though the temple attracts millions of visitors each year, you can still find a quiet place to take in the spiritual strength that emanates from the meditating Buddha statues.

About half an hour’s drive from the temple, in Magelang, is the house in which the Dutch Lieutenant De Kock arrested Indonesia’s first anti-colonial hero, Prince Diponegero, in 1830. Today, De Kock’s house is a museum and an event venue, located just a few hundred meters from Oei Hong Djien’s home.

Ever since I first visited Magelang in 2012, I have been keen to learn more about Oei Hong Djien’s art collection, which is on display at three different locations in Magelang: the collector’s home, the OHD Museum, and the Heritage House. So I can hardly believe my luck when Oei Hong Djien invites me to stay for as long as I wish, and gives me access to the collection and his library. He spends two days as my personal guide before jetting off to the opening of Europalia in Brussels, where a few works from his collection are displayed at Bozar.

Oei Hong Djien speaks to me in fluent Dutch, and as he tells me about Magelang and the special province of Yogyakarta, I sense his intense attachment to the region, which is also strongly perceptible in his art collection. Yogyakarta special province was a stronghold of the Indonesian independence movement during the revolution (1945-1949) and Oei Hong Djien (b. 1939) is one of just a few surviving witnesses of this period. He was nine years old when his family was divided: his father stayed in Magelang and the children went to Semarang, where their grandma and her family lived, to get a better education.

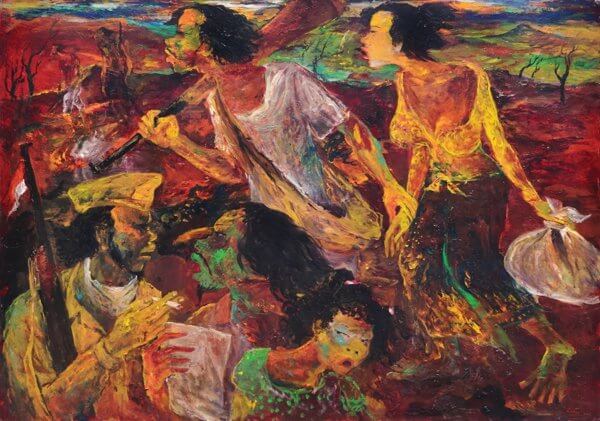

His mother had already passed away in 1942, during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch Indies. Semarang is just 75 km from Magelang, but it was too dangerous to pass the demarcation line for the family to visit each other, so they had to take the long way through East Java. This childhood experience certainly is one psychological factor that drives Oei Hong Djien’s interest in the art of the revolutionary era. His collection includes many masterpieces that relate visually to the trauma of war. One that keeps haunting my thoughts since seeing it in Oei Hong Djien’s Heritage House is Lee Man Fong’s Torture Practices By the Japanese Army, 1945.

Lee Man Fong finished this painting in 1945, the year marking the transition in Indonesia from the Japanese occupation to the Dutch government’s reclamation of the territory formerly known as the Dutch Indies. The clue to this painting came to me while reading De tolk van Java (2016), a novel by Alfred Birney.[1] The autobiographical book reveals the writer’s connection to the historical period of the 1940s through the complex figure of his father, an Indonesian interpreter called Arto Noland. Noland, who had fought brutally on different fronts for the Dutch army, emigrated to the Netherlands in the 1950s. Here is the brutal scene from Birney’s book that describes how Japanese soldiers tortured Noland because of his anti-Japanese activities:

‘Two Japs tied me to a board with thick ropes. One of them shoved a funnel into my mouth. Another kept filling the funnel with water from a bucket. I was forced to swallow the water, and I would feel my stomach swelling up, then somebody would kick me in the gut, so the water shot out of my ears, mouth, nose and anus. This torture was repeated four times, until there was blood coming out of my anus.’[2]

Birney puts into words what Lee Man Fong painted with his own idiosyncratic technique and style. Central to the painting, however, is not the man who is being tortured, but the Japanese soldier whose cruel smile betrays the pleasure he takes in fulfilling his task.

Lee Man Fong’s Torture Practices by the Japanese Army hangs on the veranda wall at the Heritage House in the city center of Magelang, not far from the OHD Museum. Oei Hong Djien’s great-grandfather came to Magelang from Xiamen in 1858. The Heritage House probably dates to the late-19th or early-20th century (the exact date is unknown), but was renovated in the 1930s. The architecture flaunts its roots in Chinese, Dutch, and Indonesian traditions. The leaded light windows are decorated with Chinese calligraphy and mythological motifs. Other interior elements like lamps, doors, floor designs, and wash basins are formally rooted in European art deco. The tropical climate is accommodated with strategically placed ventilation openings copied from Indonesian traditional architecture. The vents allow refreshing winds to circulate so that the temperature inside the house is comfortable.

Thoughtful yet energetic, Oei Hong Djien told me that in the revolutionary times, his family lived in the Heritage House. They were Christians, and when the Dutch airplanes came flying over the city, the sirens would wail and they would gather around an improvised altar. Many Christians and Chinese people were attacked or even killed during the period directly after the end of WWII. A power vacuum had emerged, and it was unclear who was responsible for enforcing law and order. Clearly the remaining Japanese soldiers were not in charge, but who was? The new Indonesian army or the Dutch military awaiting reinforcements?[3] In 1946, the newly formed government of Indonesia, led by Sukarno, relocated to the region of Yogyakarta, where they received support from the Sultan. Yogyakarta, a sultanate, still enjoys the special status of being governed by a Sultan thanks to its role in the revolution. Many artists accompanied Sukarno and fought for Indonesian independence on the frontlines of the sultanate. Magelang became a stronghold for the pro-independence movement. As Christians of Chinese descent, Oei Hong Djien’s family was seen by the Indonesian revolutionary fighters as being close to the Dutch. Even though it must have been a scary time for him, he is obviously proud to have this intense historical connection to the region.

The collector’s regional embeddedness is also strongly present in his extraordinary art collection, which includes works by representatives of the modern art movement in Indonesia such as S. Sudjojono, Hendra Gunawan, Soedibio, H. Widayat, Emiria Sunassa, Mochtar Apin, and Affandi. Many of these painters experienced the war period firsthand. The significance of the experience and trauma of war made it reappear as a subject of their paintings throughout their lives.

Among the oldest works in the art collection are paintings from the 1940s by Hendra Gunawan. Freedom Fighters (1947) depicts Tentara Nasional Indonesia soldiers firing a weapon from a strategic location, while the On the Sidewalk of Yogyakarta (1947) shows how the lives of ordinary people were affected by poverty and other consequences of war. Refugees (1949) is a powerful expressionistic scene demonstrating people’s desperate search for direction within an apocalyptic environment.

In 1997, the collector opened the OHD Museum in Central Magelang, close to the Heritage House. The museum displays a part of his collection and is a magnet for visitors from all over the world, as well as local school classes, students, researchers, and professional artists. He is proud of his collection and defends it against allegations of forgery, which is a huge topic within the art scene, by telling plausible stories about how he acquired the works. Despite his age, OHD is a regular visitor of art events in Indonesia and internationally. He is also a vivacious supporter of the contemporary cultural scene in the Yogyakarta region. If he is not off on one of his trips to visit an artist acquaintance or an international art fair, you might be lucky enough to catch him in the museum, where he enjoys talking to pupils, tourists and professional visitors alike.

My schedule allowed me to spend two weeks reading, writing, and viewing the collection. I left Magelang reloaded with energy, new ideas and a positive spirit for future projects.

[1] Birney, A. (2016). De tolk van Java: Waarin de herinneringen van een kamerolifantje, de memoires van een oorlogstolk gehamerd op een schrijfmachine, onderbroken met verhalen, brieven en gemopper van de oudste zoon, becommentarieerd door zijn broer. Breda: De Geus.

[2] Original Dutch text: ‘Twee Jappen legden me op een plank en bonden me er op vast met dikke touwen. Eén duwde een trechter in mijn mond, een ander goot met een emmer de trechter steeds vol water. Ik moest het water doorslikken, voelde mijn maag opzwellen en werd daarna hard op mijn maag getrapt, zodat het water door mijn oren, mond, neusen anus naar buiten werd geperst. Deze foltering werd viermaal herhaald, tot dat er bloed uit mijn anus kwam.’ Translation: Alana Gillespie.

[3] In Dutch, this period is called Bersiap.

My research in Indonesia was supported by the Shared Cultural Heritage Matching Fund.