For one month, between November 7 and December 7, the 8th African Photography Biennial took place in Bamako, Mali’s dusty capital. In its early editions, the Biennial mostly presented Africa’s neglected history of photography. Over the course of time, however, it also developed into a platform for artists’ views on contemporary Africa. The Bamako Encounters, as the latest Biennial was called, had ‘Borders’ as its central theme. Basically, the Biennial offered a criss-cross selection of photographic perspectives from more than 60 artists born on the African continent.

As the Biennial’s artistic directors Michket Krifa and Laura Serani explain, most of the contemporary geopolitical borders in Africa are heirs to colonial rule, and are still provoking conflicts ‘between African states, around issues of sovereignty, the distribution of economic resources or ethnic grouping’. This take on ‘Borders’ resulted in an assemblage of photographs and videos in which transnational trade, migration and the effects of war are denounced. On top of that, the Biennial comprised works engaging in ‘questions of cultural, social, national and even personal identity’, because of the fact that these issues, too, belong to the complex realities within Africa. Certainly, globalisation and identity politics do not only affect Africa, but the Bamako Encounters confines itself to showing photography focussed on this continent.

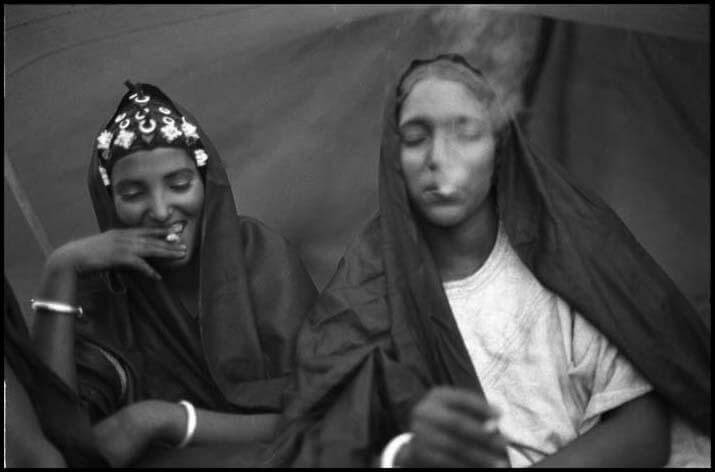

Choosing the theme of borders was an appropriate curatorial move for different reasons. For one thing, the issue of borders has local relevance in Mali itself, whose national borders were determined in 1884 at the Berlin Conference by European colonial powers. One of the tragic results of this is that the Tuareg territory has been divided into parts now belonging either to Mali or to one of its several neighbouring countries such as Algeria or Niger. To this day, the Tuaregs are struggling for the autonomy that is still withheld from them, with occasional outbursts of violence as a result. Nevertheless, despite the political sensitivity of the subject, the director of the National Museum, Samuel Sidibé, who also is the Managing Director of the biennial and the curator of the section entitled Contemporary Malian Photographers, chose to exhibit the series called The Tuaregs of Essakane, Timbuktu by Harandane Dicko. Documenting the life of the Tuaregs, Dicko’s works often transcends the documentary style of photography, which results in fascinating images like The Pleasure of Smoking.

Krifa and Serani are right when they say that ‘more than elsewhere, borders in Africa are a major issue, whether they are artificial lines drawn by men or natural barriers (rivers, mountains, deserts, oceans, etc.)’. That geopolitical borders in Africa are troublesome for the positive economical, social and cultural development of the continent is a central statement in the work of Bruno Boudjelal. His installation consisted of photographs and videos depicting details of his yet unfinished trip from Northern to Southern Africa. The works are reminiscent of stills from a full-length movie; they have the diffuse quality of a camera lens in search of a fixed point. The images and the accompanying written notes attest to his engagement with the continent, and argue for breaking down national borders, which make it extremely difficult for people to travel and do business within Africa.

Not all of the works in the Biennial celebrated the paradox of art as a bordered zone of freedom. Artists like Barthélémy Toguo and Zak Ové presented autonomous work. Toguo staged a pastiche of the stereotypical African president: a man of big words and little resolve. On the photograph entitled Stupid African President one sees a dressed-up man standing behind a prominent microphone and in front a map of Africa, while gesturing as if wanting to say: ‘Trust me, I’m serious’.

In contrast, Ové did not stage anything, but photographed people celebrating carnival. In Ové’s words, ‘a pageant inspired by the spirit of Africa’. The results were shown in the Transfigura series, with a striking work entitled The Devil is White. It depicts a black man, painted somewhat surrealistically white. This masquerade is a statement against the white slave traders who in the eighteenth century brought African people to Trinidad and forced them to abstain from their African cultural traditions. Seen in this light, Ové’s photographs are part of the celebration of creative freedom which to this day has defied the ban.

Many of the Biennial’s visitors came over from the Northern hemisphere, especially from Europe, whereas the local population seemed to rarely notice the event. Perhaps this had to do with the efforts the organisers put into bringing visitors over and making Bamako comfortable for them by providing transport, accommodations and dinners. It seemed as though the whole event was dominated by the European Union and the French Ministry for Foreign and European Affairs, the French Embassy in Mali, the French Cultural Centre in Bamako and the rest of the mostly European or multinational supporters and sponsors of the Biennial. In consideration of the historical relation between Mali and France, a bit of colonial critique would certainly be appropriate here.

All in all, the Bamako Biennial itself conveyed the impression of being secluded from the non-African world. The theme of ‘Borders’ reinforced this impression of separateness. ‘More than elsewhere,’ the curators stated, ‘borders in Africa are a major issue’. And yet, the exhibition establishes little relation to the ‘elsewhere’, so that one wonders where exactly the curators apply the standard. Kader Attia’s photograph from the Square Rocks series, which illustrates the biennial’s catalogue cover and posters, suggests a view ‘beyond Africa’. The organisers could have reduced the impression of insularity by inviting artists from other parts of the world to reflect on Africa’s borders and on what lies beyond.

Published in Metropolis M No.1 February/March 2010.

Image: Harandane Dicko, The Pleasure of Smoking, 2005