As this year’s Bamako Biennial demonstrates, photographic practice has become established in African culture and some African artists working with photography have developed a particular idiom which enables them to advance their causes. One of them is George Osodi, an artist who has taken the relation between Europe and Africa as a point of departure.

The work of the Nigerian-born Osodi, whom most will know from his participation in Roger Buergel’s documenta 12, tells about the effects of globalisation on people’s lives with great empathy: his art concerns Africa, but it also accentuates the continent’s involvement in transnational processes.

The Black Street series is an example of this. Taken in Benin City (Nigeria), Stavanger, Oslo and Amsterdam between 2008 and 2009, the images of this series tell the tragic tale of the relation between Nigerian prostitutes in Europe and their families in Nigeria. In Benin City, Osodi photographed women executing rituals supposed to bring good luck to the girls who are leaving Nigeria to work as ‘escorts’ in Europe. When I met the artist at the Biennial, he told me that for the rituals the women use substances like lemonade or chicken-blood which they rub on the girls, or pour out into the river where the liquids are supposed to flow up to the ‘white men’s land’ to protect the girls and make them rich. After the rituals, the future ‘escorts’ leave for Europe and when they succeed in arriving there, they are trafficked into prostitution. In the meantime, their families are waiting for the girls to return with lots of money to buy houses and cars for them.

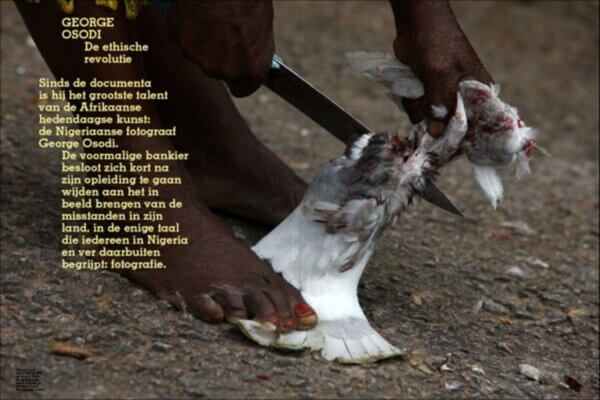

One of the images from the Black Street series is a close-up of a woman’s foot with red-painted nails standing on the wing of a dead bird so that it does not slip away while she cuts it in pieces with a large knife. The abject aspect of the depicted act evokes the idea that the act stands as a symbol for the brutality with which the families offer their daughters for money.

Another photograph shows African women standing in the rain on Stavanger’s dark streets awaiting their customers; it is taken from a distance, from the perspective of someone who hides, because the photographer had been prevented and threatened by the girls’ panders. Osodi said that the girls were also ashamed and afraid that he would exhibit the photographs in Nigeria and that their families would then see the girl’s working conditions. For this project, Osodi used the language of photography to advance the cause of what the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe has called the ‘ethical revolution’, which basically suggests a reversal of social injustices, a turning away from ‘the climate of indiscipline’ and the renunciation of corruption in Nigeria.

What interested me was how Osodi became involved in this kind of artistic activism and what he expects from it. While we were sitting in the shade somewhere around Bamako’s National Museum, the artist told me that he had grown up in Benin City, but that at a young age he had left for Lagos, where he was then trained as a banker. Being fed up with the grievances of the society surrounding him and the dissatisfaction of not doing anything against it, he one day decided to give up his job, as well as the conveniences attached to it, and to become a professional photographer. Photography had been his hobby for a while, but at this point he resolved on selling his car, buying a camera and attending photography courses.

His career as a photographer got started in 2002 when he took pictures in Lagos shortly after a tremendous explosion of a military munitions’ depot which killed over 600 people. He had been working as a photographer for the local media for some years and was pleased to learn that, after the exhibition, the Associated Press (AP) showed interest in collaborating with him, although they would not pay him as well as his European colleagues. In any case, through the AP Osodi finally got the chance to publish his photographs globally, and during our talk he emphasised that this was exactly what he wanted. Whereas the local media were hesitant about publishing photographs showing content that might embarrass the Nigerian government, the AP was uninhibited by that. At that time, he went to the Niger Delta and started to document the humanitarian and ecological situation in the region, where many foreign oil companies are present. One day, the curators Roger Buergel and Koyo Kouoh came to Lagos, where they met Osodi and selected some of his photographs for documenta 12. In Kassel, the art world opened its doors for Osodi’s work, which since then has been in demand in these circles.

Osodi grabs every opportunity to present his work, for it is a welcome possibility to bring the issues of social injustice, Nigerian lawlessness and corruption to people’s attention. For him, photography is the language which he ‘speaks’ and which he considers to be understood globally. ‘Photography speaks to everyone, not depending on the level of education,’ he told me, ‘You don’t need to be a professor to read photography.’ With regard to the given that there are around 500 spoken languages in Nigeria, one can see that Osodi considers photography a more universal language. Demonstrating his work worldwide, not only in newspapers but also in the framework of art exhibitions, is central to Osodi’s activism. This is because, in his eyes, Nigeria’s problems are not only related to the country’s bad politics, but also to the unethical attitude with which multinationals, especially oil companies, behave in Nigeria.

A work recently shown in Oslo’s National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design in the framework of the exhibition Hypocrisy: The Site-Specificity of Morality illustrates Osodi’s artistic strategy. The curators of the show, Stina Högkvist and Koyo Kouoh, had invited him for a residency period, during which he explored the way in which oil companies proceed in Norway. The resulting work was a double-screen projection of photographs of the surroundings of the oil factories and their workers in Norway and Nigeria. This installation revealed the differences between the companies’ behaviour in Africa, where they merciless exploit the workers and pollute the environment without any regard for the devastating effects, and in Europe, where they, generally speaking, conform to labour codes and the rules of pollution control. Osodi is convinced that this is not solely the fault of the oil companies’ managements, which profit from Nigeria’s bad governance. He states: ‘Corruption is based on mutual agreements.’

Osodi’s photographic projects in Oslo and Bamako are good examples of a transnational artistic activism; they are artworks telling about the relations between peoples’ everyday lives in Africa and Europe and how these lives are connected. Osodi’s photographs are reflections of what Édouard Glissant has called the ‘poetics of relation’ (1997). The Martinique-born Glissant argued for a mingling of colonial and local culture, because in his eyes such exchange has always taken place, though unfortunately it was often based on aggression and harsh exercises of power. His notion of ‘relation’ relies on the belief that ‘every community’s reasons for existence’ are equally important. This view on ‘relation’ enables Glissant to criticise the colonialist’s aggression and at the same time it opens up a way towards the appropriation of selected aspects of colonial culture. His writing is mostly concerned with language (especially Creole languages), but as the work of Osodi shows, photography is also qualified to tell tales of relation.

Though Osodi’s tales reflect the harsh reality of Nigerian people’s lives, they are also endowed with a sophisticated aesthetic that addresses the (international) viewer’s perception. These fascinating aesthetic aspects open up ways into contemporary exhibition spaces that offer Osodi a possibility for the staging of his tales. In that sense, his aesthetic activism takes advantage of the exhibition space as a podium that is protected by the concept of artistic autonomy and, paradoxically, is therefore a suitable platform for his kind of socially engaged interventions. Moreover, Osodi believes that aesthetic aspects help to attract the viewer’s attention towards the image’s content by establishing an emotional connection between viewer and image. His works do not only tell about the problematic relation between Africans and Europeans; they are also personal documents of the artist’s hope for change. Creating awareness about the economic relation between Africa and Europe and its effect on the specific Nigerian situation lies at the heart of Osodi’s artistic activism. His highest goal is to destabilise the current economic relationship between the continents, because up to now it has been based – too often and on both sides – on ignorance and greed.

Published in Metropolis M No. 1 February/March 2010